Moving into town – Kinngait, Nunavut

Monday, October 27, 2008 at 5:20AM

Monday, October 27, 2008 at 5:20AM  Or, instead of walking across a land-bridge, you can try to get there by plane.

Or, instead of walking across a land-bridge, you can try to get there by plane.

…into this treeless land of ice and snow and wind.

…into this treeless land of ice and snow and wind.

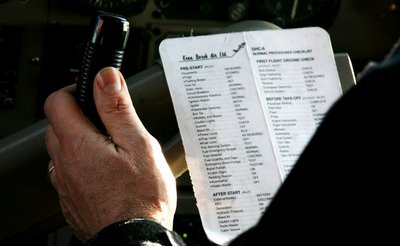

…even if Debi caught the steward/co-pilot reading through directions for take-off. Click on the photo above. You’ll see we aren’t kidding.

…even if Debi caught the steward/co-pilot reading through directions for take-off. Click on the photo above. You’ll see we aren’t kidding.

Because somehow the blonde pony-tail of our pilot consoled us, even though she didn’t seem any older than our daughters. It was good to realize that the era of Arctic bush-pilots – not that she was exactly that – wasn’t completely over.

Because somehow the blonde pony-tail of our pilot consoled us, even though she didn’t seem any older than our daughters. It was good to realize that the era of Arctic bush-pilots – not that she was exactly that – wasn’t completely over.

Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut, seemed more ephemeral than a hunting camp.

Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut, seemed more ephemeral than a hunting camp.

Because of permafrost, buildings have to be stilted above the ground.

Because of permafrost, buildings have to be stilted above the ground.

And the land itself seems perplexed by the mere idea of town.

And the land itself seems perplexed by the mere idea of town.

Like all towns in Ninavut, Kinngait is a new invention. Kinngait’s colonial name is Cape Dorset. It’s sixty years old.

Like all towns in Ninavut, Kinngait is a new invention. Kinngait’s colonial name is Cape Dorset. It’s sixty years old.

While Inuit have been living nomadically in hunting camps in Nunavut for over 4,000 years.

This doesn’t mean that we didn’t find Kinngait’s modern incarnation full of charm.

This doesn’t mean that we didn’t find Kinngait’s modern incarnation full of charm.

And its people utterly delightful.

And its people utterly delightful.

But that also doesn’t wash away the fact that something crucial is being lost.

But that also doesn’t wash away the fact that something crucial is being lost.

But we already living our own modernized lives have no right to wash our hands free of our own responsibilities – and we have no right to expect people like the Inuit to hold for us our own nostalgia for our own lost connections to the land.

But we already living our own modernized lives have no right to wash our hands free of our own responsibilities – and we have no right to expect people like the Inuit to hold for us our own nostalgia for our own lost connections to the land.

In 1913 the Hudson Bay Company built a trading post in Kinngait to facilitate their own trading for furs, and as Inuit families and hunting groups gradually moved closer to the post, a more settled community began to emerge.

In 1913 the Hudson Bay Company built a trading post in Kinngait to facilitate their own trading for furs, and as Inuit families and hunting groups gradually moved closer to the post, a more settled community began to emerge.

Not that the Inuit missed the irony and significance of this transition. This is carver and photographer Peter Pitseolak. He has deliberately posed with a qakivak in one hand (a long-handled fishing spear) and a rifle in the other.

Not that the Inuit missed the irony and significance of this transition. This is carver and photographer Peter Pitseolak. He has deliberately posed with a qakivak in one hand (a long-handled fishing spear) and a rifle in the other.

On a hillside above Kinngait, there is a memorial cairn to three men: Ashoona, Saila, and Potoogook (the namesake of our guide on Mallikjuag).

On a hillside above Kinngait, there is a memorial cairn to three men: Ashoona, Saila, and Potoogook (the namesake of our guide on Mallikjuag).

The arrival of these three men with their hunting groups is considered the start of the community in Kinngait – the beginning of a new era. And among the new skills required of these founders was knowledge of how to deal with qallunaat, white people from the south.

Saila, one of these three founders, was the father of Pauta Saila, whom we introduced to you in our last blog.

Saila, one of these three founders, was the father of Pauta Saila, whom we introduced to you in our last blog.

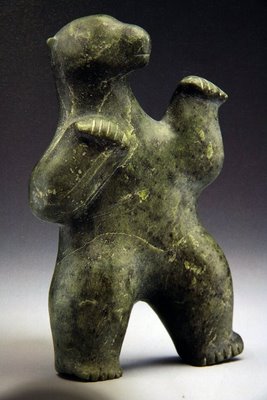

Here is one more of Pauta’s dancing bears.

And carver and printmaker Kananginak Pootoogook is the son of one of the other three founders. This means that Kananginak and Pauta are direct links between a life of nomadic hunting and town life. And it means that their art has created a path for a younger generation.

And carver and printmaker Kananginak Pootoogook is the son of one of the other three founders. This means that Kananginak and Pauta are direct links between a life of nomadic hunting and town life. And it means that their art has created a path for a younger generation.

When Kananginak was still living in an outpost camp, he found a walrus tusk and carved a bird on it. He gave it to his father to sell in town. When his father returned, he brought back five bullets for Kananginak in trade.

Now Kananginak’s carvings and prints appear in galleries and museums around the world.

It is impossible to explain how one small community like Kinngait, whose population is perhaps 1400, could produce so many thriving artists.

It is impossible to explain how one small community like Kinngait, whose population is perhaps 1400, could produce so many thriving artists.

But one partial explanation lies in how long the Inuit have so skillfully used their hands. If men and women could not have made and mended their clothes and gear at a moment’s notice out on the land – their kamiik (boots), avataq (sealskin floats), and so many other things – they simply would not have survived.

So these hands…

…chisel a stonecut like this, which in turn…

…chisel a stonecut like this, which in turn…

We suppose some might want to argue with the transition to a modern tool.

We suppose some might want to argue with the transition to a modern tool.

This is a loon by Etulu Etidloi, the father of Isaci Etidloi, whose sculpture a man could die at any time we showed you in our last blog.

You see the generational passing of this art.

The Inuit first carved mainly on ivory and traded with the occasional whaling ships passing through.

The Inuit first carved mainly on ivory and traded with the occasional whaling ships passing through.

Even when Kinngait was on its way towards becoming a settled town, it was still an exciting moment when a dog-team would arrive and as a family unfurled sealskins, among the furs there might also be a carved masterwork or two, by now perhaps carved in local serpentine that can range in color from yellow-green to nearly black.

The above photo was taken at an Inuit campsite about 1964.

In the 1950’s disease ran through Qimmiit, Inuit dogs, and the Canadian government undertook, or ordered to be undertaken, wholesale slaughters of the dogs, purportedly for public health reasons.

In the 1950’s disease ran through Qimmiit, Inuit dogs, and the Canadian government undertook, or ordered to be undertaken, wholesale slaughters of the dogs, purportedly for public health reasons.

The connection between the Inuit and Qimmiit would be hard to over-emphasize. One could not have survived without the other.

The connection between the Inuit and Qimmiit would be hard to over-emphasize. One could not have survived without the other.

"My grandmother often told me that I am still alive today because of our Qimmiit," Paulusie Cookie from Umiujaq said.

The slaughtering of the dogs remains a controversy. In the post-WW II era, military activity was “setting up the Distant Early Warning line across the North to protect North America from attack.” The northern mining industry was booming, and a young Canadian government feared the possibility of larger powers trying to annex these sparsely populated lands.

The slaughtering of the dogs remains a controversy. In the post-WW II era, military activity was “setting up the Distant Early Warning line across the North to protect North America from attack.” The northern mining industry was booming, and a young Canadian government feared the possibility of larger powers trying to annex these sparsely populated lands.

And there are those who still fear the dogs were slaughtered to force the Inuit from their nomadic hunting lives into fixed settlements.

And there are those who still fear the dogs were slaughtered to force the Inuit from their nomadic hunting lives into fixed settlements.

This history leaves big questions – and not just for Kinngait.

This history leaves big questions – and not just for Kinngait.

Perhaps one way to frame the question is this: how can our life in town stay connected with the land – and with the spirit of our ancestors who have lived on the land before us?

Perhaps one way to frame the question is this: how can our life in town stay connected with the land – and with the spirit of our ancestors who have lived on the land before us?

Or in other words, how can Cape Dorset stay connected with Mallikjuag?

But this is a question we have to own in our own lives – and not just expect that it’s a responsibility that people like the Inuit should carry for the rest of us.

But this is a question we have to own in our own lives – and not just expect that it’s a responsibility that people like the Inuit should carry for the rest of us.

The best way we’ve heard the question asked is by poet Robert Hass:

The best way we’ve heard the question asked is by poet Robert Hass:

“How do you re-animate a world denuded by western positivist science?”

The last time we saw Hass, he didn’t have answers to his own good question.

Cape Dorset,

Cape Dorset,  Kinngait,

Kinngait,  Nunavut | in

Nunavut | in  Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage