West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative – Kinngait, Nunavut

Sunday, November 9, 2008 at 9:26AM

Sunday, November 9, 2008 at 9:26AM

In 1948 and 1949 artist and writer Jim Houston made his first trips to Nunavut. The carvings he saw fascinated him, and he learned that the Inuit had been carving for generations – amulets, talismans, tools for hunting. But he also saw other small pieces that had no apparent function, except that they were pleasing – pieces we would call art, even though in Inuktitut, as in many other aboriginal languages, there is no word for art.

In 1948 and 1949 artist and writer Jim Houston made his first trips to Nunavut. The carvings he saw fascinated him, and he learned that the Inuit had been carving for generations – amulets, talismans, tools for hunting. But he also saw other small pieces that had no apparent function, except that they were pleasing – pieces we would call art, even though in Inuktitut, as in many other aboriginal languages, there is no word for art. Houston also saw that in the changing Arctic the Inuit were having difficulty coming in from the land and adjusting to life in settlements.

Houston also saw that in the changing Arctic the Inuit were having difficulty coming in from the land and adjusting to life in settlements.

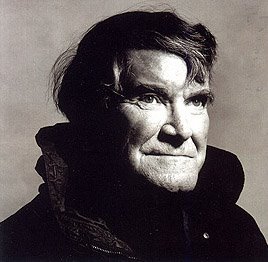

And he made a 260-mile dogsled trek to Kinngait to meet carver Osuitok Ipeelee. Osuitok did carvings enthusiastically for Houston and then gave his approval to Houston's idea for supporting Inuit art.

And he made a 260-mile dogsled trek to Kinngait to meet carver Osuitok Ipeelee. Osuitok did carvings enthusiastically for Houston and then gave his approval to Houston's idea for supporting Inuit art.

Houston deliberately paid Osuitok the then princely sum of $50 for a caribou carving. He wanted to get other Inuits’ attention. And he did.

Houston deliberately paid Osuitok the then princely sum of $50 for a caribou carving. He wanted to get other Inuits’ attention. And he did.

That carving by Osuitok is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Another one of Osuitok's elegant caribou appears above.

Soon after Osuitok and Houston's initial collaboration, what came to be called the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative was born. It has been in existence for fifty years now, and in addition to lithography and stonecut studios in Kinngait, it also operates a grocery and a supply store in town and administers government community service contracts. All in all, it is the first or second largest employer in Kinngait.

Soon after Osuitok and Houston's initial collaboration, what came to be called the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative was born. It has been in existence for fifty years now, and in addition to lithography and stonecut studios in Kinngait, it also operates a grocery and a supply store in town and administers government community service contracts. All in all, it is the first or second largest employer in Kinngait.

It also independently markets the work of its co-operative members through its distribution center, Dorset Fine Arts, in Toronto.

It also independently markets the work of its co-operative members through its distribution center, Dorset Fine Arts, in Toronto.

Current WBEC printmakers on their coffee break in “512,” the room that was the original center for the co-operative’s arts activity, so named because “512” was the original square footage of the center.

Current WBEC printmakers on their coffee break in “512,” the room that was the original center for the co-operative’s arts activity, so named because “512” was the original square footage of the center.

Terry Ryan’s involvement with the co-operative has also been instrumental – and ongoing. He’s on the left in this photo with Inuit leader Simonie on the right. The photo was taken in an Inuit camp in 1964.

Terry Ryan’s involvement with the co-operative has also been instrumental – and ongoing. He’s on the left in this photo with Inuit leader Simonie on the right. The photo was taken in an Inuit camp in 1964.

But the co-operative is wholly owned by its members -- all of whom are residents of Kinngait and almost all of whom are of Inuit descent.

But the co-operative is wholly owned by its members -- all of whom are residents of Kinngait and almost all of whom are of Inuit descent.

Jimmy Manning (on left) is the studio manager of the co-operative. He is also a photographer, writer, carver, and painter. Palaya Qiatsug (right) directs the purchasing of carvings.

Jimmy Manning (on left) is the studio manager of the co-operative. He is also a photographer, writer, carver, and painter. Palaya Qiatsug (right) directs the purchasing of carvings.

Palaya is a carver himself. Among his favorite themes are shamanic transformations. He considers himself a “traditionalist with a mission.”

Palaya is a carver himself. Among his favorite themes are shamanic transformations. He considers himself a “traditionalist with a mission.”

The mission is to communicate traditional Inuit culture to the young.

The mission is to communicate traditional Inuit culture to the young.

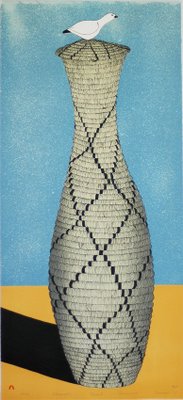

Each year since 1958 the co-operative has produced a collection of Cape Dorset prints. They only produce 50 sets of these prints, and this year’s collection was just about to appear when we arrived. We had had a sneak preview at Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto.

Each year since 1958 the co-operative has produced a collection of Cape Dorset prints. They only produce 50 sets of these prints, and this year’s collection was just about to appear when we arrived. We had had a sneak preview at Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto.

And when we arrived in Kinngait (Cape Dorset), the co-operative was already working towards next year’s collection…

And when we arrived in Kinngait (Cape Dorset), the co-operative was already working towards next year’s collection…

…including doing color samples on a print by renowned artist Kenojuak Ashevak.

…including doing color samples on a print by renowned artist Kenojuak Ashevak.

We'll introduce you to Kenojuak in our next blog.

We'll introduce you to Kenojuak in our next blog.

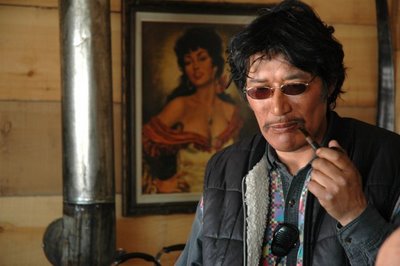

Kenojuak’s son Arnaqurk is an accomplished artist in his own right, part of a generation doing innovative new work. Arnaquak works as a lithographer.

Kenojuak’s son Arnaqurk is an accomplished artist in his own right, part of a generation doing innovative new work. Arnaquak works as a lithographer.

And he has been called “possibly the most creative and exciting sculptor in Cape Dorset today.” He is a constructivist and works with different materials at once. He thinks less of what might be taken away from stone and more of what might be added. When he walks outside of town, or qajaqs, he might find bone or glass or baleen or antler that he'll later add to stone.

And he has been called “possibly the most creative and exciting sculptor in Cape Dorset today.” He is a constructivist and works with different materials at once. He thinks less of what might be taken away from stone and more of what might be added. When he walks outside of town, or qajaqs, he might find bone or glass or baleen or antler that he'll later add to stone.

It's when he begins to do his own work that the ideas arise.

The braintrust gathered in the lithography studio.

The braintrust gathered in the lithography studio.

Painter, photographer, and printmaker Bill Ritchie from Newfoundland comes to Kinngait three times a year for about a month at a time to help advise in the lithography studio.

Painter, photographer, and printmaker Bill Ritchie from Newfoundland comes to Kinngait three times a year for about a month at a time to help advise in the lithography studio.

We flew up to Kinngait with Bill, and he helped introduce us to WBEC and the Kinngait community.

As did Jimmy Manning, who manages the stonecut studio.

As did Jimmy Manning, who manages the stonecut studio.

Jimmy is also a guide. If we come back during summer, he'll take us out traveling in his boat. We can stay at two heated, comfortable cabins he has far from town. Then beyond the cabins, we'll be traveling and camping as the old ones did. There's a catch in his voice as he tells us this.

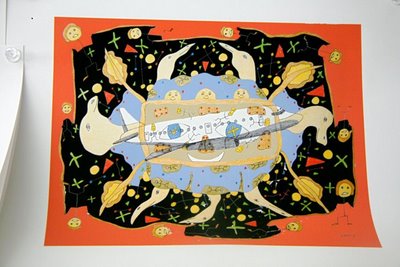

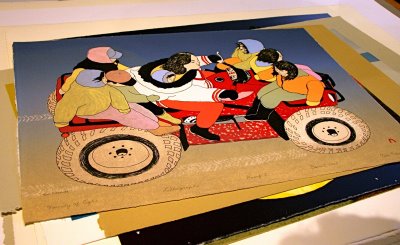

Sometimes, Jimmy says, it's perfectly clear that a drawing wants to become a lithograph. This is one of Kananginak's prints from the current 2008 print collection.

Sometimes, Jimmy says, it's perfectly clear that a drawing wants to become a lithograph. This is one of Kananginak's prints from the current 2008 print collection.

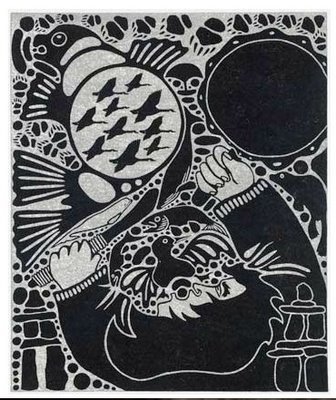

And sometimes it’s equally clear that an image wants to become a stonecut print…

And sometimes it’s equally clear that an image wants to become a stonecut print…

…with tools and materials beautiful in their own right…

…with tools and materials beautiful in their own right…

So that this begins to happen.

So that this begins to happen.

Qavavau Manumie is a multi-talented artist who cuts and prints stone blocks by day and who draws and carves at night and on weekends.

Qavavau Manumie is a multi-talented artist who cuts and prints stone blocks by day and who draws and carves at night and on weekends.

His images often appear in Cape Dorset Annual Print Collections, and when they do, Qavavau has undertaken every step of the process himself: drawing the original image, carving the block, making the prints.

Here are drawings of Qavavau’s which might appear in next year’s Cape Dorset Print Collection.

Here are drawings of Qavavau’s which might appear in next year’s Cape Dorset Print Collection.

Click on the images and look closely…

Click on the images and look closely…

…and you’ll begin to perceive the wit and irony in them.

…and you’ll begin to perceive the wit and irony in them.

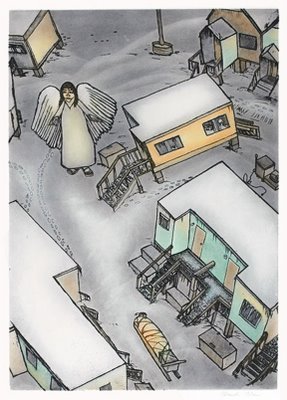

Shuvinai Ashoona’s drawings and prints derive from her own idiosyncratic perceptions as well.

Shuvinai Ashoona’s drawings and prints derive from her own idiosyncratic perceptions as well. Inuit gather eggs from the tundra along the rocky shoreline. Of course, the eggs also hatch, and Shuvinai says that “Eggs that come out from the earth -- from the vapor of the earth – are more interesting than seeing the inside of the egg.”

Inuit gather eggs from the tundra along the rocky shoreline. Of course, the eggs also hatch, and Shuvinai says that “Eggs that come out from the earth -- from the vapor of the earth – are more interesting than seeing the inside of the egg.”

Shuvinai's print above is titled An angel in town. Notice the waiting, empty dogsled. Is someone arriving -- or about to leave?

Shuvinai's print above is titled An angel in town. Notice the waiting, empty dogsled. Is someone arriving -- or about to leave?

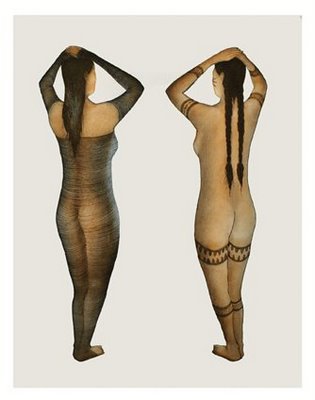

Oviloo Tunnillie carves from a very personal point of view…

Oviloo Tunnillie carves from a very personal point of view…

…often graceful feminine figures.

…often graceful feminine figures.

And she often treats controversial subjects that others avoid, like alcoholism and domestic abuse.

And she often treats controversial subjects that others avoid, like alcoholism and domestic abuse.

These aren’t all of Kinngait’s artists, of course – let alone the work of all Inuit communities.

These aren’t all of Kinngait’s artists, of course – let alone the work of all Inuit communities.

Nor, of course, are all issues smoothly resolved. This print, “Shamanizing,” is by Aoodla Pudlat from Baker’s Lake.

Nor, of course, are all issues smoothly resolved. This print, “Shamanizing,” is by Aoodla Pudlat from Baker’s Lake.

And the edge of old conflicts can still be sharp.

And the edge of old conflicts can still be sharp.

You’ll see the irony in how Karoo Ashevak’s “Harpooned Shaman” becomes its own crucifixion.

And there’s a dwindling pool of artists drawing and printmaking now. You can make more money more quickly from a carving than from the time a drawing requires.

And there’s a dwindling pool of artists drawing and printmaking now. You can make more money more quickly from a carving than from the time a drawing requires.

These are all issues that Isuma, an independent Inuit film production group in Igloolik, explores in their work -- and not only by documenting Inuit culture.

These are all issues that Isuma, an independent Inuit film production group in Igloolik, explores in their work -- and not only by documenting Inuit culture.

For instance, The Journals of Knud Rasmussen tells the story of the great Inuit shaman Aua as it was recorded by the Danish explorer/adventurer Knud Rasmussen. It is a story of how “…Shamanism was replaced with Christianity – and the balance of life was changed forever.” Isuma founder Zacharias Kunuk says that the film “tries to answer two questions that haunted me my whole life: Who were we? And what happened to us?”

For instance, The Journals of Knud Rasmussen tells the story of the great Inuit shaman Aua as it was recorded by the Danish explorer/adventurer Knud Rasmussen. It is a story of how “…Shamanism was replaced with Christianity – and the balance of life was changed forever.” Isuma founder Zacharias Kunuk says that the film “tries to answer two questions that haunted me my whole life: Who were we? And what happened to us?”

Isuma’s earlier, award-winning Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner) is available on Netflix.

Kunuk says, “We live on an island that we’ve inhabited for 4000 years…After we brought in television and cable, now everybody’s glued to the tube. And that’s where we (Isuma) wanted to be, so our little company started to bring back the storytelling…”

Kunuk says, “We live on an island that we’ve inhabited for 4000 years…After we brought in television and cable, now everybody’s glued to the tube. And that’s where we (Isuma) wanted to be, so our little company started to bring back the storytelling…”

So Isuma is using this new medium as a means of recovering traditional Inuit storytelling. And it is also functioning as a collaborative community effort – the lifeway upon which the Inuit have always depended for survival.

Again, Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto is the distribution center for the West Baffin Eskimo Co-Operative. They sell Inuit work to galleries around the world.

Again, Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto is the distribution center for the West Baffin Eskimo Co-Operative. They sell Inuit work to galleries around the world.

We -- Red Egg Gallery -- will be working with them, too.

We -- Red Egg Gallery -- will be working with them, too.

This means that if you find something in their catalogue that you are interested in…

This means that if you find something in their catalogue that you are interested in…

…let us know and you can purchase it through Red Egg Gallery.

We know this is the first time we’ve specifically mentioned Red Egg Gallery’s function of selling artists’ work -- and we hope we’re making our own intention clearer: to serve the integrity of nature, community, and wisdom in local communities around the world.

We know this is the first time we’ve specifically mentioned Red Egg Gallery’s function of selling artists’ work -- and we hope we’re making our own intention clearer: to serve the integrity of nature, community, and wisdom in local communities around the world.

We’re hoping to connect you with artists, work, communities, histories – and places – that you love, too.

We’re hoping to connect you with artists, work, communities, histories – and places – that you love, too. (The history of WBEC above came through our conversations with its members whom we mention above -- and from Cape Dorset Sculpture by Derek Norton and Nigel Reading – with an introduction by Terry Ryan.)

(The history of WBEC above came through our conversations with its members whom we mention above -- and from Cape Dorset Sculpture by Derek Norton and Nigel Reading – with an introduction by Terry Ryan.)