Stone, spiral, book (I)

Tuesday, December 16, 2008 at 4:12AM

Tuesday, December 16, 2008 at 4:12AM

In truth, we’ve been traveling in a world of stone for a long time now.

In truth, we’ve been traveling in a world of stone for a long time now.

After all, that would have meant they pre-dated the origin of the universe as a whole.

Perhaps this was because the human presence was so self-evident. Perhaps it was because what sites of ritual once wanted to record was not “look, we, too, are here” – but rather, the elemental wholeness within which humans once found themselves.

An elemental wholeness not lost to all of us, it is true.

An elemental wholeness not lost to all of us, it is true.

For instance, this is one of the most striking places that we know – back home in the Sur. And all during this current journey that we’re on, this stone keeps calling out to us.

In fact, there are striking architectural similarities.

Right now you’re standing in the nave in the east, looking west. Over the shoulder of architect Franco Valente is the base of the altar stone. Below that is the window to the crypt.

Photo by Ken Williams, from Newgrange.com

Photo by Ken Williams, from Newgrange.com

The 5,000 year old passage tomb at Newgrange is aligned with the sun as well. But it is aligned with the winter solstice.

Precisely aligned.

Here is an overall map of some of the major monuments in Brú na Bóinne. You'll see the Newgrange passage tomb in the center. And again, its own passageway -- depicted in the photo above the map -- is exactly aligned with sunrise on the winter solstice.

And the interiors of both passage tomb and cathedral are generally cruciform in their floor plans.  In this aerial plan of the crypt of Epyphanius, the tomb is that of the abbot Epyphanius. Below the tomb is the window into the crypt that you saw before.

In this aerial plan of the crypt of Epyphanius, the tomb is that of the abbot Epyphanius. Below the tomb is the window into the crypt that you saw before.

So the sun runs the length of the nave from the east, passes through the window over the tomb, and then strikes the western wall.

Specifically, it strikes a fresco of Christ – in angelic form from the book of the Apocalypse.

Specifically, it strikes a fresco of Christ – in angelic form from the book of the Apocalypse.

That figure is above my head, flanked from left to right by Gabriel, Raphael, Michael, and Uriel. Obviously, this is interior electric light, so you don’t get the solar equinoctial effect.

Now you’re looking north down into the crypt yourself. The image of Christ is on the back wall to your left. And the tomb – and window into the crypt – is in the recess to your right.

Now you’re looking north down into the crypt yourself. The image of Christ is on the back wall to your left. And the tomb – and window into the crypt – is in the recess to your right.

In the interior chambers of passage tombs like Newgrange, there are ritual basins that can remind you of birthing stones or baptismal fonts. They feel “feminine” -- places for water in the darkness – as interior complements to the solar alignment of the whole.

In the interior chambers of passage tombs like Newgrange, there are ritual basins that can remind you of birthing stones or baptismal fonts. They feel “feminine” -- places for water in the darkness – as interior complements to the solar alignment of the whole.

And as you bow and crouch and move inside along the passageway, without noticing it, your feet are moving along a precisely calculated incline.

And as you bow and crouch and move inside along the passageway, without noticing it, your feet are moving along a precisely calculated incline.

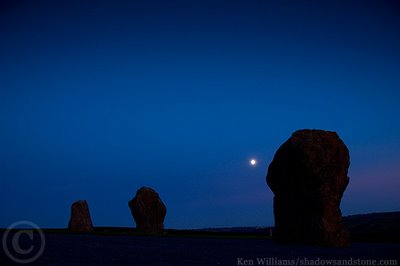

Photo by Ken Williams, from shadowsandstone.com

Photo by Ken Williams, from shadowsandstone.com

OK. So let’s imagine it. It’s winter solstice night.

Only a small group of elders or priests can fit inside the small interior chamber. The rest of the people wait outside under the open sky – with prayer and fire and dance and chant.

It is the greatest festival of the year.

But you are one of those inside – waiting in utter darkness in a small stone room that feels like a tomb.

But you are one of those inside – waiting in utter darkness in a small stone room that feels like a tomb.

Then you begin to notice it. A thread of light is creeping along the floor of the narrow passageway.

Then you begin to notice it. A thread of light is creeping along the floor of the narrow passageway.

It reaches the beehive central chamber and diffuses into a honey-glow.

Then a moment later, exactly at 8.52, the thread strikes the center of the recessed back wall like an arrow from the heart of light itself.

The light in the chamber lasts for exactly seventeen minutes.

The light in the chamber lasts for exactly seventeen minutes.

You’ve been waiting for it all year.