Our last blog was about leaving a place, but that was a long time ago.

Our last blog was about leaving a place, but that was a long time ago.

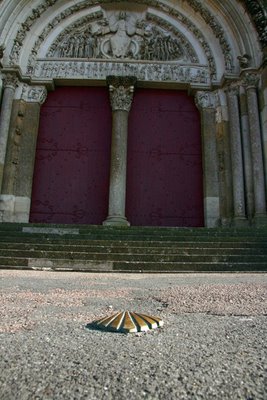

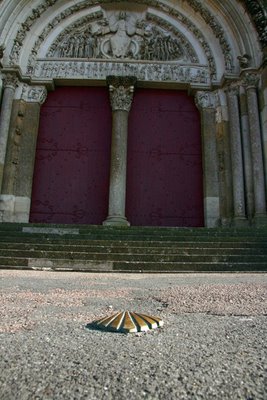

When we arrived in Vézelay (France), we found ourselves being led to a room in a prayer-house with this view of the basilica.

When we arrived in Vézelay (France), we found ourselves being led to a room in a prayer-house with this view of the basilica.

Tradition says that relics of Sainte Marie-Madeleine are in the crypt here.

Tradition says that relics of Sainte Marie-Madeleine are in the crypt here.

And Vézelay has remained one of the most important points along the pilgrimage route through France to Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

And Vézelay has remained one of the most important points along the pilgrimage route through France to Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

But to tell you how we arrived here, we have to go back quite a bit.

In fact, like Marcel Proust, perhaps we should go all the way back to childhood.

In fact, like Marcel Proust, perhaps we should go all the way back to childhood.

This is Proust’s room in his aunt’s house in the village of Illiers, where he used to go for summers as a child – and which he transformed into Combray in Á la Recherche du Temps Perdu.

This is Proust’s room in his aunt’s house in the village of Illiers, where he used to go for summers as a child – and which he transformed into Combray in Á la Recherche du Temps Perdu.

Á la Recherche du Temps Perdu has been called a novel of the self.

But don’t we all write novels of the self ?

But don’t we all write novels of the self ?

A madeleine. Perhaps a little armagnac. And we are on our way.

In 1971, the hundred year anniversary of Proust’s birth, Illiers renamed itself Illiers-Combray.

In 1971, the hundred year anniversary of Proust’s birth, Illiers renamed itself Illiers-Combray.

But even when you’re walking in the streets of Illiers, you sense that Combray has always been more real than Illiers – and that, as Proust says, his novel is an optical lens wherein each of us might read ourselves.

But even when you’re walking in the streets of Illiers, you sense that Combray has always been more real than Illiers – and that, as Proust says, his novel is an optical lens wherein each of us might read ourselves.

He also said his novel was like a cathedral – which is another lens through which we might read ourselves.

He also said his novel was like a cathedral – which is another lens through which we might read ourselves.

But let’s not go as far back as childhood – at least not yet.

But let’s not go as far back as childhood – at least not yet.

Let’s go back to the island of Iona instead.

Let’s go back to the island of Iona instead.

Iona is one of the important places on this journey we haven't talked about yet,

Iona is one of the important places on this journey we haven't talked about yet,

…one of those places that feel like they will never leave you.

…one of those places that feel like they will never leave you.

Even when you cannot keep pace with yourself, they still remain waiting for you faithfully – waiting for you to dip that madeleine into a little tea or armagnac.

Even when you cannot keep pace with yourself, they still remain waiting for you faithfully – waiting for you to dip that madeleine into a little tea or armagnac.

And we keep landing in places that ask for a lifetime to begin to know them.

And we keep landing in places that ask for a lifetime to begin to know them.

So how can you keep pace with that?

Debi keeps saying, "Come on, let’s go – or else we’ll never reach all the important places we want to go."

Debi keeps saying, "Come on, let’s go – or else we’ll never reach all the important places we want to go."

Of course, there’s always one more photograph to be taken.

Of course, there’s always one more photograph to be taken.

"Can I photograph your sheep?“ Debi asks the crofter.

We wish we could play for you his Scottish answer. It would be worth more than all these other words.

He called his dogs,

He called his dogs,

…and in short order

…and in short order

…all the sheep

…all the sheep

were front and center

were front and center

…while all the time I was thinking,

…while all the time I was thinking,

"Are you really so sure there’s anywhere else we want to go?"

"Are you really so sure there’s anywhere else we want to go?"

And both of us feel that way about Iona.

And both of us feel that way about Iona.

Of course, you‘d have to wish away the relatively modern, restored 13c abbey – because it wasn’t there when Columcille arrived in 563 ce.

Of course, you‘d have to wish away the relatively modern, restored 13c abbey – because it wasn’t there when Columcille arrived in 563 ce.

St. Columba is Columcille‘s name -- Latinized.

St. Columba is Columcille‘s name -- Latinized.

And if you could travel back to the Iona of his day, what you would see would be beehive-shaped timber and turf cells, surrounded on three sides by the vallum, a low stone and earth wall to mark the precinct of the Celtic monastery.

And if you could travel back to the Iona of his day, what you would see would be beehive-shaped timber and turf cells, surrounded on three sides by the vallum, a low stone and earth wall to mark the precinct of the Celtic monastery.

The fourth side to the monastery is the sea.

The monastic cells wouldn’t have looked quite like this caseal which is old enough, but of course it isn’t timber and turf. All that would’ve burnt back to the good earth long ago.

The monastic cells wouldn’t have looked quite like this caseal which is old enough, but of course it isn’t timber and turf. All that would’ve burnt back to the good earth long ago.

Nor for the same reason would they look exactly like St. Gallerus‘ oratorio on the Dingle peninsula in Ireland.

Nor for the same reason would they look exactly like St. Gallerus‘ oratorio on the Dingle peninsula in Ireland.

But click on the photo and look at the genius of this architecture. Not a spit of mortar. No roof-cribbing. Just precisely hand-laid, tiered stone -- watertight for a milennium.

But on Iona, what you still can see is the vallum, even 1400 years later. It’s the diagonal line in the earth just beyond the grazing sheep.

But on Iona, what you still can see is the vallum, even 1400 years later. It’s the diagonal line in the earth just beyond the grazing sheep.

And if you would have crossed these waters a couple centuries after Columcille did, you’d have found a cluster of high crosses around his tomb – to mark the important pilgrimage site.

And if you would have crossed these waters a couple centuries after Columcille did, you’d have found a cluster of high crosses around his tomb – to mark the important pilgrimage site.

Tradition says that his tomb was where the small chapel in the 13c abbey is now – which you step into through the small doorway in the upper left of this photo.

And tradition says that Columcille’s own cell was on the very knoll before you – Tor Abb.

And this high cross has been keeping watch here for 1200 years.

And this high cross has been keeping watch here for 1200 years.

High crosses are sacred markers.

High crosses are sacred markers.

They connect heaven and earth – and fuse pre-Christian and Christian elements.

They arise in the ancient lineage of menhirs, standing stones.

They arise in the ancient lineage of menhirs, standing stones.

Some say that once there may have been more than 300 high crosses on the small island of Iona.

Some say that once there may have been more than 300 high crosses on the small island of Iona.

Perhaps that number is an exaggeration.

But still there can be little doubt that Iona is a very thin place

But still there can be little doubt that Iona is a very thin place

…which means that here you can pass between this world and another as easily as dusk.

They say that Columcille washed ashore at Port a’ Churaich – the Port of the Coracle.

They say that Columcille washed ashore at Port a’ Churaich – the Port of the Coracle.

Perhaps he left his beloved Ireland in penance for partisanship in a dynastic battle. He belonged to a lineage of Irish kings.

And this is a familiar Celtic motif: to embark on a pilgrimage as penitence.

So the two of us made our own pilgrimage-within-a-pilgrimage as well – from Tor Abb to Port a' Churaich.

So the two of us made our own pilgrimage-within-a-pilgrimage as well – from Tor Abb to Port a' Churaich.

Not a step of the way is marked. Not one sign or letter or arrow anywhere. You have to find your way feelingly.

Not a step of the way is marked. Not one sign or letter or arrow anywhere. You have to find your way feelingly.

And yet this is the most named landscape that we know.

But the names are wisps that someone has spoken into the air, and that then someone else has re-spoken, until you begin to hear them, too – and then, at least for this one day, you can begin to leave history behind as well.

Many places have two names existing side-by-side -- or else one overlays the other. But the older one is still visible and percolates from below like a spring or holy well or foundation stones.

Many places have two names existing side-by-side -- or else one overlays the other. But the older one is still visible and percolates from below like a spring or holy well or foundation stones.

A hillock is Sithean Mor – "the big fairy mound.“

A hillock is Sithean Mor – "the big fairy mound.“

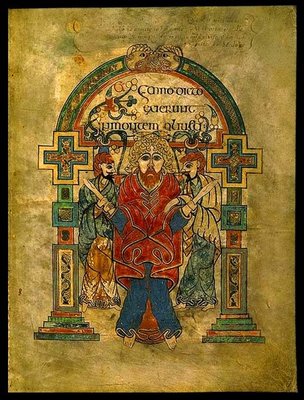

It is also Cnoc nan Aingeal, "Hill of the Angels,“ because Columcille would go there to pray, and one night, against Columcille’s wishes, a monk had followed him, and from a distance had seen Columcille visited by angels while he prayed upon the hill.

Often Columcille would best, or correct, Druid wizards with his own spiritual power, which came from God.

Often Columcille would best, or correct, Druid wizards with his own spiritual power, which came from God.

But Columcille often appears like a Christian wizard himself – with telekinetic powers and prophecy and the healing of bodies and souls.

One of the traditions in Celtic monasticism is for a monk to set out upon the sea in a coracle without any oars at all, accepting wherever the sea and the good Lord would take him.

One of the traditions in Celtic monasticism is for a monk to set out upon the sea in a coracle without any oars at all, accepting wherever the sea and the good Lord would take him.

It is thought, for instance, that St. Brendan the Navigator, or his followers, reached Vineland, which archaeologists make out to have been Newfoundland, more than 800 years before Columbus reached the continent.

Undoubtedly, Brendan sailed in a relatively bigger, wooden boat.

Undoubtedly, Brendan sailed in a relatively bigger, wooden boat.

But the curaichs themselves were framed with pliable slender branches, and then they were covered with hides that tautened around the frame as they dried from their initial soaking.

But the curaichs themselves were framed with pliable slender branches, and then they were covered with hides that tautened around the frame as they dried from their initial soaking.

A curraich is one of those simple, elemental creations so elegant that it takes your breath away

A curraich is one of those simple, elemental creations so elegant that it takes your breath away

…and so seaworthy that it can still stand up to fierce Hebrides currents and weather.

…and so seaworthy that it can still stand up to fierce Hebrides currents and weather.

Now they are covered with canvas, not hides. But you can still press your fingers between the ribbing and feel how thin the shell is

Now they are covered with canvas, not hides. But you can still press your fingers between the ribbing and feel how thin the shell is

…and then shake your head in wonder at the sea-journeys made within them.

…and then shake your head in wonder at the sea-journeys made within them.

The technical similarities between curraichs and Celtic monastic cilles and oratorios might have already occurred to you – in addition to affinities with the watercraft and dwellings of other indigenous people around the world.

When you arrive at Port a' Churaich,

When you arrive at Port a' Churaich,

…what you see, and what is immediately apparent,

…what you see, and what is immediately apparent,

...is how beautiful the stones are – and how rugged is the sea.

...is how beautiful the stones are – and how rugged is the sea.

Pilgrims build cairns and other markers here.

Pilgrims build cairns and other markers here.

We left simple ones, as well.

The tradition is that you find two stones for yourself. One stone you choose for something that is binding you or holding you back -- something you need to let go of.

The tradition is that you find two stones for yourself. One stone you choose for something that is binding you or holding you back -- something you need to let go of.

That stone you throw into the sea.

That stone you throw into the sea.

The other stone you choose as some resolve or intention or inherent goodness within yourself that you want to keep and deepen. That stone you carry home with you.

The other stone you choose as some resolve or intention or inherent goodness within yourself that you want to keep and deepen. That stone you carry home with you.

It’s not part of the tradition, but we threw and kept many stones for you. Not that we’d presume to know what you’d want to be freed of, and what you’d want to deepen,

It’s not part of the tradition, but we threw and kept many stones for you. Not that we’d presume to know what you’d want to be freed of, and what you’d want to deepen,

…but "Scott,"one of us would call, or "Robin," and another beautiful stone would go far out to sea – and its twin within a pocket.

On Iona, you can learn all four seasons in a single day.

On Iona, you can learn all four seasons in a single day.

And the island has been writing its own novel of the self longer than there has been anyone to remember it.

And the island has been writing its own novel of the self longer than there has been anyone to remember it.

And just when you think you’ve mastered the grammar of stone and sea and cille and solitary cobbled shore

And just when you think you’ve mastered the grammar of stone and sea and cille and solitary cobbled shore

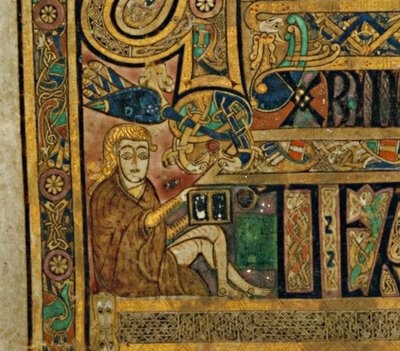

…you have to master this as well – that next to his monastic cell Columcille had a writing hut as well,

…you have to master this as well – that next to his monastic cell Columcille had a writing hut as well,

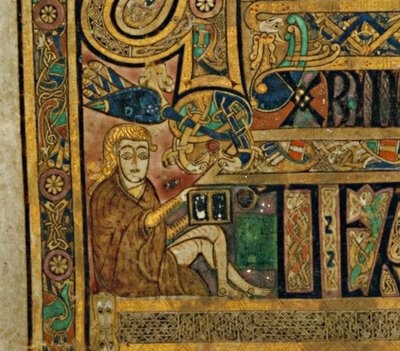

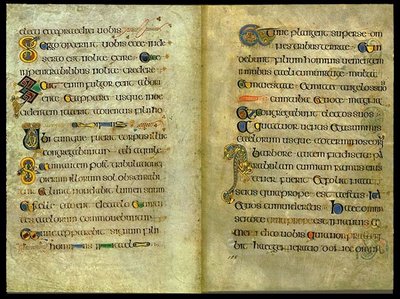

…and that Iona, or I Chalium Cille, or simply I (as the island has variously called itself) has written the most beautiful book the western world has ever known.

…and that Iona, or I Chalium Cille, or simply I (as the island has variously called itself) has written the most beautiful book the western world has ever known.

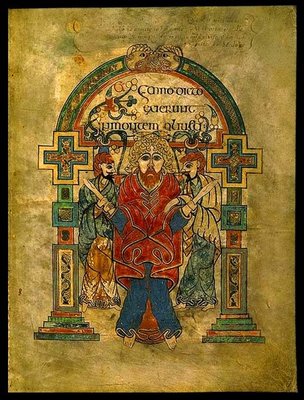

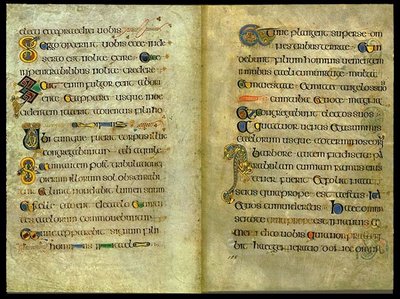

The Book of Kells.

Umberto Eco calls The Book of Kells "the product of a cold-blooded hallucination.“

Umberto Eco calls The Book of Kells "the product of a cold-blooded hallucination.“

Scholars know that the illuminated manuscript, probably written about 800 CE, ended up at the Columban monastery of Kells in Ireland after the Vikings raided Iona.

Scholars know that the illuminated manuscript, probably written about 800 CE, ended up at the Columban monastery of Kells in Ireland after the Vikings raided Iona.

But they don’t know if the book was begun at Iona and finished at Kells – or if it had already been completed at Iona. But either way, it was transported from Iona to Kells in a curraich for safety.

Inseparable from I, I Chalium Cille, Iona, the manuscript is another place where the world is thin.

Inseparable from I, I Chalium Cille, Iona, the manuscript is another place where the world is thin.

At Trinity College library in Dublin, for security reasons, they never announce in advance the day when they will turn another page for you to view.

At Trinity College library in Dublin, for security reasons, they never announce in advance the day when they will turn another page for you to view.

It doesn’t matter.

You can wait there for the page to turn as happily as upon any shore.

You can wait there for the page to turn as happily as upon any shore.

The two of arrived back at Tor Abb late at night and went into the abbey for compline.

The two of arrived back at Tor Abb late at night and went into the abbey for compline.

The story didn’t end there, though,

The story didn’t end there, though,

…because the island keeps writing chapters even when you sleep.

…because the island keeps writing chapters even when you sleep.

Sources:

1. Personal visits. Iona: November 6-8, 2008. Book of Kells at Trinity College, Dublin, November 21, 2008.

2.Adomnán, Life of St. Columba.

3. The Book of Kells CD-ROM. Trinity College Library, Dublin.

4. Bernard Meehan, The Book of Kells.

5. Geoff Holder, The Guide to Mysterious Iona and Staffa.

Sunday, June 1, 2014 at 10:57PM

Sunday, June 1, 2014 at 10:57PM  The steeple of Saint HilaireMore left of Combray than I had imagined five years ago in winter when the town of Illiers had seemed so tawdry in comparison with what emerged from the taste of a few crumbs of madeleine in a spoonful of tea.

The steeple of Saint HilaireMore left of Combray than I had imagined five years ago in winter when the town of Illiers had seemed so tawdry in comparison with what emerged from the taste of a few crumbs of madeleine in a spoonful of tea.

Aunt Leonie's house.

Aunt Leonie's house. The bell on the gate that only Swann would ring.

The bell on the gate that only Swann would ring. The clapper that would rattle when anyone else would enter.

The clapper that would rattle when anyone else would enter. The siphon coffee system Uncle Adolphe loved to use.

The siphon coffee system Uncle Adolphe loved to use. The hawthorns along Swann's way.

The hawthorns along Swann's way.

Tansonville.

Tansonville. M. Vinteuil's along the Guermantes' way.

M. Vinteuil's along the Guermantes' way.

Combray,

Combray,  Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust