Scottish friends and artists

Tuesday, February 24, 2009 at 3:49PM

Tuesday, February 24, 2009 at 3:49PM  In this blog, we’ll only be able to introduce our Scottish friends to you and to suggest some thematic affinities in their work – not that they comprise anything like a conscious school or group. But even they were surprised in re-visiting each other’s studios to see what common currents were running among them.

In this blog, we’ll only be able to introduce our Scottish friends to you and to suggest some thematic affinities in their work – not that they comprise anything like a conscious school or group. But even they were surprised in re-visiting each other’s studios to see what common currents were running among them.

One immediate thing that struck us was their common innate sense of the organic continuity between their own creative processes…

One immediate thing that struck us was their common innate sense of the organic continuity between their own creative processes…

…and nature’s creative process as a whole.

…and nature’s creative process as a whole.

They need to hold these beings in their hands intimately.

They need to hold these beings in their hands intimately.

You have to make. With joy and reverence you have to become a conscious and active element in the ferment of the whole yourself.

You have to make. With joy and reverence you have to become a conscious and active element in the ferment of the whole yourself.

Does love come first? Dante once had asked.

Does love come first? Dante once had asked.

Or does vision?

(Click on the image to read the texts.)

We met Frances Law while we were still back home in California.

We met Frances Law while we were still back home in California.

We met her through her work, which we saw on-line and immediately loved.

We met her through her work, which we saw on-line and immediately loved.

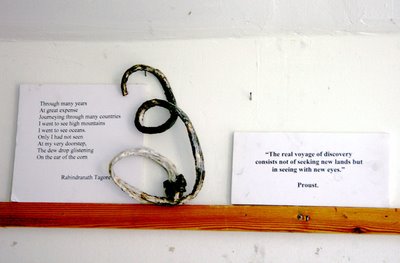

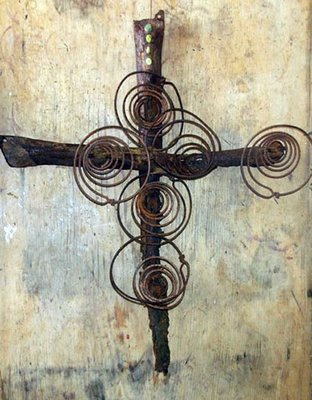

This assemblage is titled Over the Ocean.

Even before we had met Fran and her husband John in person, they had set out for us an itinerary through the archaic west coast of Scotland that brought us to Iona.

Even before we had met Fran and her husband John in person, they had set out for us an itinerary through the archaic west coast of Scotland that brought us to Iona.

That was no accident.

Fran walks and works the liminal Scottish coast.

Fran walks and works the liminal Scottish coast.

And she and John and their children Uist and Rowan are on Iona as faithfully as a season.

And she and John and their children Uist and Rowan are on Iona as faithfully as a season.

Fran doesn’t find and adfix things.

Fran doesn’t find and adfix things.

And it isn’t an accident that her assemblages remind you of archaeological findings.

And it isn’t an accident that her assemblages remind you of archaeological findings.

The archaeology is within ourselves.

The archaeology is within ourselves.

Fran is retracing layers and layers of our own history,

…which means that she is re-connecting us with stone and earth and bone and sea.

…which means that she is re-connecting us with stone and earth and bone and sea.

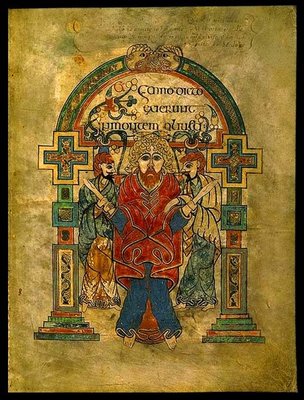

If you read our last blog, you’ll be able to gloss this work yourself. It’s called St. Columba’s Tears.

If you read our last blog, you’ll be able to gloss this work yourself. It’s called St. Columba’s Tears.

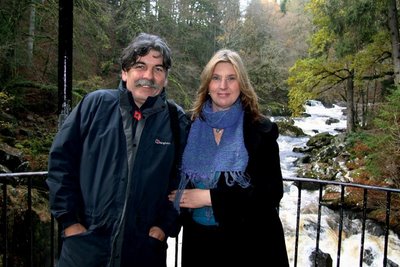

Before we had ever met them, Fran and John had invited us to stay in their Birnam flat in Perthshire.

Before we had ever met them, Fran and John had invited us to stay in their Birnam flat in Perthshire.

That’s Birnam as in Birnam Wood from Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

That’s Birnam as in Birnam Wood from Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

And why not?

Tradition says that Macbeth and Duncan were both buried on Iona, as have been many other Scottish kings.

Tradition says that Macbeth and Duncan were both buried on Iona, as have been many other Scottish kings.

Birnam and nearby Dunkeld were our first respite from traveling.

Birnam and nearby Dunkeld were our first respite from traveling.

This meant that from being wanderers suddenly we had become villagers again.

This meant that from being wanderers suddenly we had become villagers again.

When we left Dunkeld, John mailed two mixes of Scottish songs and ballads which were to meet us later on the continent.

When we left Dunkeld, John mailed two mixes of Scottish songs and ballads which were to meet us later on the continent.

…and be right back in Dunkeld to type these lines to accompany Debi’s photographs for you.

…and be right back in Dunkeld to type these lines to accompany Debi’s photographs for you.

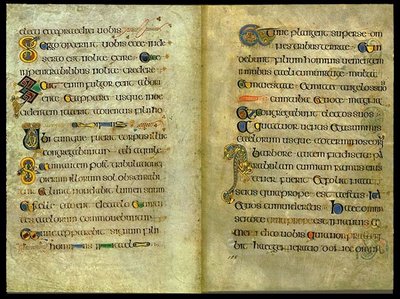

There is sometimes a literary element in Kyra Clegg’s work

There is sometimes a literary element in Kyra Clegg’s work

…and a narrative thread that weaves together a series whose interrelationships have been deeply felt.

…and a narrative thread that weaves together a series whose interrelationships have been deeply felt.

For instance, Kyra has composed a series called Cabinets for Emily that suggest 19c "curiosity" or "wonder" cabinets that present Kyra's own "collection of things seen in the life and poetry of Emily Dickinson."

For instance, Kyra has composed a series called Cabinets for Emily that suggest 19c "curiosity" or "wonder" cabinets that present Kyra's own "collection of things seen in the life and poetry of Emily Dickinson."

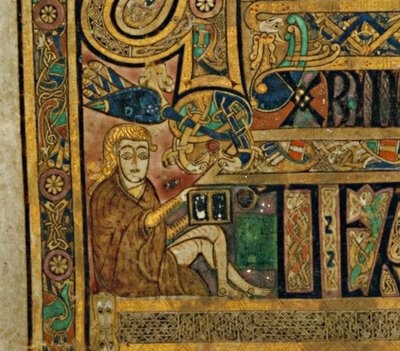

We hadn’t left Iceland all that long before we met Kyra, and so when we saw a series she had composed with a poet, based on the imagined visions of an Icelandic seeress, it felt like the images and words suspirated from a land both ancient and familiar.

We hadn’t left Iceland all that long before we met Kyra, and so when we saw a series she had composed with a poet, based on the imagined visions of an Icelandic seeress, it felt like the images and words suspirated from a land both ancient and familiar.

"Stone"

The smooth quartz pebbles

of our sightless eyes

are seeking you out.

By magnetite and lodestone

we summons you home.

We call you from the burial-mound

with song, and a sweet pipe-tune

-- we, the skull and thigh bone.

You need to look long and deeply for all the interrelationships to arise.

You need to look long and deeply for all the interrelationships to arise.

And you want to look that long.

And you want to look that long.

Images (like the images in our own dreams) are skittish beings. We need to give each the time it needs in order to understand the whole.

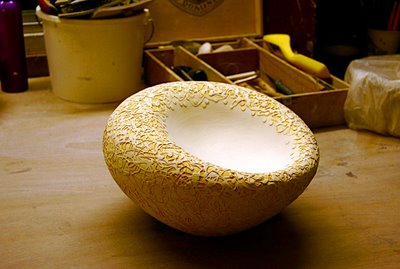

Shona Leitch gathers and holds and shapes as well. Here her sculptor’s hands are already shaping out of thin air.

Shona Leitch gathers and holds and shapes as well. Here her sculptor’s hands are already shaping out of thin air.

She watches organic and geological processes and sees where and how she might enter in.

She watches organic and geological processes and sees where and how she might enter in.

Perhaps it’s a sculpture that might rest inside a dwelling,

Perhaps it’s a sculpture that might rest inside a dwelling,

…or an organic and composed landscape outside.

…or an organic and composed landscape outside.

Everything seems to whorl like the DNA and galactical spins that are at the heart of things.

Everything seems to whorl like the DNA and galactical spins that are at the heart of things.

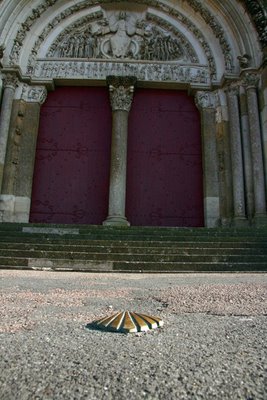

Like Fran Law’s paintings of shells

Like Fran Law’s paintings of shells

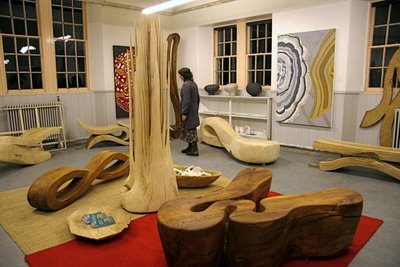

…and Nigel Ross’s wood sculptures.

…and Nigel Ross’s wood sculptures.

…and Claudia Wegner are partners. (Claudia is on the left -- with Shona Leitch).

…and Claudia Wegner are partners. (Claudia is on the left -- with Shona Leitch).

Nigel and Claudia didn’t wonder much how their respective work would look if they placed it together in their workplace.

Among other things, Claudia is an expert on fungus, collaborating with the leading Scottish and British scientific experts in the field of medicinal mycology. An exhibition of her work has just opened at Dundee University. Its aim is to portray the complex beauty of fungi and their medicinal and therapeutic values.

Among other things, Claudia is an expert on fungus, collaborating with the leading Scottish and British scientific experts in the field of medicinal mycology. An exhibition of her work has just opened at Dundee University. Its aim is to portray the complex beauty of fungi and their medicinal and therapeutic values.

"Trees and wood are a theme that has run through my life," Nigel says.

"Trees and wood are a theme that has run through my life," Nigel says.

He was happiest as a child running wild in Hertfordshire woodlands. Later his family moved to Arran Island in Scotland, where Nigel worked in various forestry fields.

He sculpts beautiful and unexpected abstract forms from the lengths of fallen trees – work that appears in homes, woodlands, parks, and gardens across Europe and the US.

He sculpts beautiful and unexpected abstract forms from the lengths of fallen trees – work that appears in homes, woodlands, parks, and gardens across Europe and the US.

And there is a functionality in his work that arises from the abstract design, rather than conflicting with it.

Don’t worry. Your body will find that function

Don’t worry. Your body will find that function

...if you allow it its own natural spontaneity. And time.

...if you allow it its own natural spontaneity. And time.

Sources

We could only introduce these friends and artists to you in this blog. To see more of their work, visit their websites.

Perthshire | in

Perthshire | in  Artists

Artists