Perhaps you’ve already made this journey,

Perhaps you’ve already made this journey,

…or did you think the opportunity had passed you by some time ago,

…or did you think the opportunity had passed you by some time ago,

…perhaps lost back in the 60’s along with so many other things,

…perhaps lost back in the 60’s along with so many other things,

…when you were reading Herman Hesse in your dorm room, or a decade or so later, Thomas Merton’s The Asian Journals?

…when you were reading Herman Hesse in your dorm room, or a decade or so later, Thomas Merton’s The Asian Journals?

Or perhaps the archetypal East has already traveled west to visit you.

Or perhaps the archetypal East has already traveled west to visit you.

And actually we’re mid-air ourselves right now, even as we type,

And actually we’re mid-air ourselves right now, even as we type,

…wearing the khata the Tibetan Guesthouse gave us

…wearing the khata the Tibetan Guesthouse gave us

…when we left Kathmandu.

…when we left Kathmandu.

Just the day before, I had picked up this Smithsonian magazine from the reading table.

Just the day before, I had picked up this Smithsonian magazine from the reading table.

“Look at this place,” I said to Debi. “Why don’t we go here next?”

“Look at this place,” I said to Debi. “Why don’t we go here next?”

But in the meantime, ever since we had been in India, we'd been mulling over the question of the ashram.

But in the meantime, ever since we had been in India, we'd been mulling over the question of the ashram.

“What is an ashram?” artist Jyoti Sahi asked. He's been asking himself this question for most of his life.

“What is an ashram?” artist Jyoti Sahi asked. He's been asking himself this question for most of his life.

In India, we stayed in three ashrams. Actually, two were not-quite ashrams – which brings us right back to Jyoti's question again.

In India, we stayed in three ashrams. Actually, two were not-quite ashrams – which brings us right back to Jyoti's question again.

Shantivanam in Tamil Nadu is a Christian Ashram, founded by French priests Parama Arubi Ananda (Jules Monchanin) and Abhishiktananda (Henri Le Saux).

Shantivanam in Tamil Nadu is a Christian Ashram, founded by French priests Parama Arubi Ananda (Jules Monchanin) and Abhishiktananda (Henri Le Saux).

But the most recognizable figure associated with Shantivanam is Benedictine monk Fr. Bede Griffiths.

But the most recognizable figure associated with Shantivanam is Benedictine monk Fr. Bede Griffiths.

Father Bede arrived in 1968. With Bede’s presence and teachings, Shantivanam became known around the world.

Father Bede arrived in 1968. With Bede’s presence and teachings, Shantivanam became known around the world.

In 1980, Shantivanam became part of the Camaldolese congregation, which makes it particularly dear to us.

In 1980, Shantivanam became part of the Camaldolese congregation, which makes it particularly dear to us.

We will have more to say about our own connection with the Camaldolese in future blogs.

We will have more to say about our own connection with the Camaldolese in future blogs.

The aim of Shantivanam is to establish a contemplative life that is based both on the tradition of Christian monasticism and on Hindu Sannyasa.

The aim of Shantivanam is to establish a contemplative life that is based both on the tradition of Christian monasticism and on Hindu Sannyasa.

The Vedas, Christian scriptures, and other sacred texts are all studied,

…while the community follows the customs of a Hindu ashram,

…while the community follows the customs of a Hindu ashram,

…wearing saffron-colored robes,

…wearing saffron-colored robes,

…sitting on the floor,

…sitting on the floor,

…and eating with the hand,

…and eating with the hand,

…according to the character of voluntary poverty which has always marked the Hindu sannyasi.

…according to the character of voluntary poverty which has always marked the Hindu sannyasi.

We fell into the rhythm of Shantivanam easily and with delight -- so perhaps now we can say something about Jyoti's question after all,

We fell into the rhythm of Shantivanam easily and with delight -- so perhaps now we can say something about Jyoti's question after all,

...namely, that an ashram is a place where meditation can begin to permeate your whole life

...namely, that an ashram is a place where meditation can begin to permeate your whole life

…so that even jaunts outside the ashram, like into the nearby village of Kulithalai,

…so that even jaunts outside the ashram, like into the nearby village of Kulithalai,

…become just an extension of that ashram life.

…become just an extension of that ashram life.

At Shantivanam, liturgy holds Hindu and Christian resonances together naturally,

At Shantivanam, liturgy holds Hindu and Christian resonances together naturally,

...so that prayer and meditation and yoga all feel like one integral practice again -- native to one's own place,

...so that prayer and meditation and yoga all feel like one integral practice again -- native to one's own place,

...and you realize once again that a life of common prayer carries you along much more surely than an airliner ever could.

...and you realize once again that a life of common prayer carries you along much more surely than an airliner ever could.

And you remember everything --

And you remember everything --

…the sandalwood paste in the morning on your face or hands,

…the sandalwood paste in the morning on your face or hands,

…the purple powder, Kumkumum, symbol of the third eye, at midday,

…the purple powder, Kumkumum, symbol of the third eye, at midday,

…and ashes, Vibhuti, when daylight has closed its own eyes, too.

…and ashes, Vibhuti, when daylight has closed its own eyes, too.

And each day, everything – each of the four elements and your own body, too – are offered back to their Creator in one great prayer of fire,

And each day, everything – each of the four elements and your own body, too – are offered back to their Creator in one great prayer of fire,

…within this rhythm in which friendships

…within this rhythm in which friendships

…bloom as easily

…bloom as easily

…as flowers.

…as flowers.

Actually, we’re right back in India even as we type this line. But perhaps you think that a lounge in the airport at Delhi – where you’ve landed in transit from Nepal – is a far cry from ashram life.

Actually, we’re right back in India even as we type this line. But perhaps you think that a lounge in the airport at Delhi – where you’ve landed in transit from Nepal – is a far cry from ashram life.

But we still haven’t answered Jyoti’s question, have we?

We also visited the Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry.

We also visited the Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry.

We don’t have the time to explain all the dimensions of Sri Aurobindo’s thought and life. But perhaps you know yourself

...that Aurobindo was an important revolutionary figure in the early part of the 20c in India.

...that Aurobindo was an important revolutionary figure in the early part of the 20c in India.

He was also a poet, a breakthrough interpreter of the Vedas, and the developer of what he called integral yoga.

He held together both India’s ancient non-dual mysticism, which he believed was his country’s unique gift to the world, and a western view of the evolutionary nature of human consciousness.

He held together both India’s ancient non-dual mysticism, which he believed was his country’s unique gift to the world, and a western view of the evolutionary nature of human consciousness.

When the rising elemental shakti energy rises through the chakras, it will be met by the descent of a divine consciousness that Aurobindo called the Super-mind.

When the rising elemental shakti energy rises through the chakras, it will be met by the descent of a divine consciousness that Aurobindo called the Super-mind.

This descent will mark an evolutionary quantum leap in human consciousness.

In the last decades of his life, Aurobindo withdrew into seclusion to dedicate himself to bringing this event to life within himself.

In the last decades of his life, Aurobindo withdrew into seclusion to dedicate himself to bringing this event to life within himself.

We visited Aurobindo’s Ashram, but we didn’t stay there. We stayed at Auroville instead.

We visited Aurobindo’s Ashram, but we didn’t stay there. We stayed at Auroville instead.

When Aurobindo withdrew into seclusion, the day-to-day direction and teaching in the ashram passed to “the Mother,” Aurobindo’s spiritual consort, whom both he and their disciples believe to be an embodiment of the Universal Mother.

When Aurobindo withdrew into seclusion, the day-to-day direction and teaching in the ashram passed to “the Mother,” Aurobindo’s spiritual consort, whom both he and their disciples believe to be an embodiment of the Universal Mother.

Auroville is the Mother’s dream of a place dedicated to Aurobindo’s principles – and a place where a community might live in a kind of geometry of peace...

Auroville is the Mother’s dream of a place dedicated to Aurobindo’s principles – and a place where a community might live in a kind of geometry of peace...

…a place that might await -- and rise up, as it were – to meet the descent of the divine.

…a place that might await -- and rise up, as it were – to meet the descent of the divine.

So we hung out

So we hung out

…and bombed around Auroville awhile.

…and bombed around Auroville awhile.

It is an agreeable place to be

It is an agreeable place to be

…with enough creature comforts to keep westerners appeased.

…with enough creature comforts to keep westerners appeased.

It is true, though, that even the abstract idea of a guru makes many of us nervous ipso facto -- let alone when the Mother is gazing out at you so ubiquitously in Auroville.

It is true, though, that even the abstract idea of a guru makes many of us nervous ipso facto -- let alone when the Mother is gazing out at you so ubiquitously in Auroville.

But you don’t exactly take exception to anything you’ve heard her say. It must just be the sense of devotion to a human that puts your teeth on edge.

But you don’t exactly take exception to anything you’ve heard her say. It must just be the sense of devotion to a human that puts your teeth on edge.

And Auroville can feel like a soap-bubble separated from the poverty of the Tamil villages that surround it,

And Auroville can feel like a soap-bubble separated from the poverty of the Tamil villages that surround it,

…separated in a way that Shantivanam never is.

…separated in a way that Shantivanam never is.

The center of Auroville is the Matrimandir – a place for concentration, for consciousness alone.

The center of Auroville is the Matrimandir – a place for concentration, for consciousness alone.

Yes, from the outside the Matrimandir looks like a slightly flattened golden golf ball, but its interior is an architectural wonder.

Yes, from the outside the Matrimandir looks like a slightly flattened golden golf ball, but its interior is an architectural wonder.

You aren’t allowed to bring cameras inside -- and you must follow certain step-by-step requirements even to be allowed inside yourself – so Debi can’t regale you with photographs of the interior.

And long as we surfed, we only came up with a one or two good pirated interior photographs.

And long as we surfed, we only came up with a one or two good pirated interior photographs.

And here’s a sketch of an early plan of the interior. Perhaps you get the drift: the long spiral ascent, the spareness inside, the opening through which light can always descend to strike the crystal in the upper, inner chamber.

And here’s a sketch of an early plan of the interior. Perhaps you get the drift: the long spiral ascent, the spareness inside, the opening through which light can always descend to strike the crystal in the upper, inner chamber.

The Matrimandir is supposed to be a place left free from any religious practice or method. Leave all that outside.

The Matrimandir is supposed to be a place left free from any religious practice or method. Leave all that outside.

Sit in the inner chamber and concentrate on your consciousness alone.

Inside, you might feel a little like you’re wearing a white-jumpsuit in some futuristic Woody Allen world. But the Matrimandir’s cool. Literally.

Inside, you might feel a little like you’re wearing a white-jumpsuit in some futuristic Woody Allen world. But the Matrimandir’s cool. Literally.

The inner chamber is air-conditioned. And in Tamil Nadu towards the end of June, just before the monsoons hit, this is no small matter.

We could have meditated in that inner chamber for a long, long time.

Though it sounds like we're only writing tongue-in-cheek now, that isn't altogether true. Yes, we did smuggle in a couple (Christian) mantras of our own.

Though it sounds like we're only writing tongue-in-cheek now, that isn't altogether true. Yes, we did smuggle in a couple (Christian) mantras of our own.

But we found the Matrimandir a good place to sit, quite on its own – and our own humble practices were helped by it.

By the way, as we’re typing on board a plane again, the flight path now reads with names like these: Kabul, Samarkand, Tashkent, Ust’ Kamenogorsk, Novosibirsk.

By the way, as we’re typing on board a plane again, the flight path now reads with names like these: Kabul, Samarkand, Tashkent, Ust’ Kamenogorsk, Novosibirsk.

Are we at least hovering around Jyoti’s question? What is an ashram anyway?

Are we at least hovering around Jyoti’s question? What is an ashram anyway?

We visited Jyoti and his wife Jane as our last stop in India.

Jyoti is an artist who has always been concerned with the interplay of art and spirituality.

Jyoti is an artist who has always been concerned with the interplay of art and spirituality.

He was with Bede at Kurisumalam Ashram before Bede had came to Shantivanam, and he has been friends with people like Lorrie Baker, the Quaker architect who overturned presumptions about what waste really means in housing designs

…for the affluent

…for the affluent

…and for the poor.

…and for the poor.

Among his many interests, Jyoti has studied the idea of ashram, which is a word that Rabindore Tagore’s father first used. Jyoti has studied Tanner communities and sarvodaya, Gandhi’s “village-based ashram movement of social transformation.”

Among his many interests, Jyoti has studied the idea of ashram, which is a word that Rabindore Tagore’s father first used. Jyoti has studied Tanner communities and sarvodaya, Gandhi’s “village-based ashram movement of social transformation.”

The aim of sarvodaya is “an awakening of everyone.”

The aim of sarvodaya is “an awakening of everyone.”

It was these Gandhian communities that brought Jane from Britain to India when she was 18. She made one return-trip to Britain, then came right back to India, where she and Jyoti have created this life together in the village of Silvapura outside Bangalore.

It was these Gandhian communities that brought Jane from Britain to India when she was 18. She made one return-trip to Britain, then came right back to India, where she and Jyoti have created this life together in the village of Silvapura outside Bangalore.

There are four stages of ashrama, Jyoti says, that match the stages of our own life.

There are four stages of ashrama, Jyoti says, that match the stages of our own life.

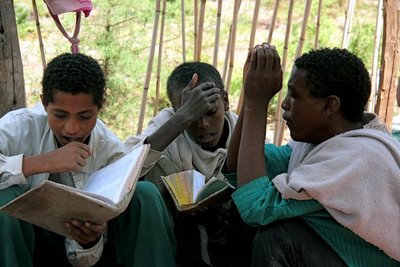

Student-life comes first. This is the stage of gaining the necessary knowledge for both our material and spiritual life.

Then comes householder-life – when we raise and care for our families.

Then comes householder-life – when we raise and care for our families.

The third stage is vanaprastha -- a pilgrim’s life, a life of semi-retirement from the world, the forest-wanderer’s life.

The third stage is vanaprastha -- a pilgrim’s life, a life of semi-retirement from the world, the forest-wanderer’s life.

Merton thought he was in this stage when he made his journey to the east in 1968, that momentous year -- the year when Bede had come to Shantivanam, too.

“Is this the stage we’re entering, too?” Debi and I asked ourselves.

“Is this the stage we’re entering, too?” Debi and I asked ourselves.

The fourth stage is sannyasa, the great renunciation of every worldly tie and aspiration so that one can make the final turn towards God alone. One assumes the kavi habit then.

The fourth stage is sannyasa, the great renunciation of every worldly tie and aspiration so that one can make the final turn towards God alone. One assumes the kavi habit then.

On our way to India, we were told, “You have to visit Jyoti’s art ashram.”

On our way to India, we were told, “You have to visit Jyoti’s art ashram.”

Did that person misspeak – or not?

“We haven’t been an ashram,” Jane says, “ but we like to think we’ve kept a certain openness.”

“We haven’t been an ashram,” Jane says, “ but we like to think we’ve kept a certain openness.”

Indeed, friends and guests, often artists, have come and stayed for months and years --in one case, for fifteen years.

Jyoti and Jane created an art center for artists and students,

Jyoti and Jane created an art center for artists and students,

...and in 1975, they built a school for the village that Jane continues to direct, raise funds for, and teach in herself.

...and in 1975, they built a school for the village that Jane continues to direct, raise funds for, and teach in herself.

When we met her, she had just returned from a two-week trip visiting schools in Chicago, Seattle, and San José.

Their grown children have gravitated back to this extended home. One son and his wife direct the art center now.

Their grown children have gravitated back to this extended home. One son and his wife direct the art center now.

Another daughter and her husband are wood-sculptors.

And she teaches art to inner city kids who come from Bangalore.

And she teaches art to inner city kids who come from Bangalore.

The gravitational center of this life has always been a focus upon the meeting-point of art, spirituality, culture, and education,

The gravitational center of this life has always been a focus upon the meeting-point of art, spirituality, culture, and education,

…and from a relaxed concentration upon this meeting-point – and from Jyoti's and Jane's differing but compatible personal gifts -- a life has emerged as organically as any Matrimandir.

…and from a relaxed concentration upon this meeting-point – and from Jyoti's and Jane's differing but compatible personal gifts -- a life has emerged as organically as any Matrimandir.

Perhaps this is the practice, the integral yoga, for householders such as we are.

Perhaps this is the practice, the integral yoga, for householders such as we are.

And Father Bede, for one, believed that householder-spirituality would be crucial for the world's future.

Now the flight-path on the screen in the plane reads: Reykavik

Now the flight-path on the screen in the plane reads: Reykavik

…and Baffin Island,

…and Baffin Island,

…which means we’re spinning west and homeward once again,

…which means we’re spinning west and homeward once again,

…though we’ll have to discover what home means to us now, since we’ve come to believe, as Basho writes, that

…though we’ll have to discover what home means to us now, since we’ve come to believe, as Basho writes, that

“Each day is a journey,

“Each day is a journey,

“…and the journey itself is home.”

“…and the journey itself is home.”

Tuesday, December 15, 2009 at 12:10AM

Tuesday, December 15, 2009 at 12:10AM